The conclusions I made then (and have been arguing for several years) have not changed, and probably won't unless the private sector halts attempted deleveraging and starts adding debt in a sustained way. Such renewed debt growth is possible (Australia seems to have achieved it, though how sustained it will be is unclear) but there is no evidence of it yet for the US, and the odds are strongly against it given the fundamental forces in play. (Note, the theme of deleveraging has become a more mainstream view, as for example exemplified by this McKinsey report on the global debt bubble and its consequences.) Anyway, as of December, US consumer credit (which doesn't include mortgage debt) is contracting at a record rate:

Consumer credit is a key gauge, but total private sector debt is still being reduced too, as shown in the graphs in my summary of the last Fed Flow of Funds report in December.

In this post I'll attempt a condensed summary and update of the prior post on treasuries plus add in some relevant third party perspectives.

The Historical Record

Government bond yields declined during both the Great Depression in the US and in Japan since its bubbles burst around 1990. These represent two different resolutions to debt bubbles — debt deflation amid severe depression, or large ongoing government stimulus and slow semi-stagnant growth as private sector debt is serviced and reduced. We are currently tracking closer to the latter scenario, but the former is still a real risk. Both scenarios were friendly to government debt prices in the past. More details and charts are in the old post.

Inflation?

The Federal Reserve cannot create inflation in consumer prices or wages (see here for one of many explanations of why... or read my prior post). The Treasury can create inflation with sufficient deficit spending, but future attempts at fiscal stimulus large enough to do so are at significant risk of political gridlock.

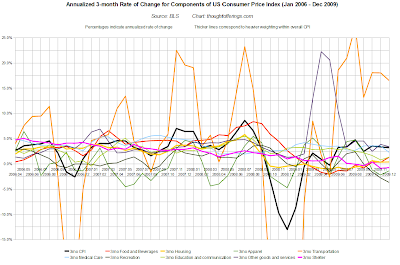

And the actual outcome so far? Look at the price level trend as of December 2009 in the chart below (from this deflation watch post). The increases (since the plunge at the end of 2008) shown by the red line are losing momentum and flattening out earlier than occurred in Japan. If the current sell-off in commodities and risk assets intensifies (prices have been looking bubbly!), the already stalling CPI changes could be shocked back into negative month on month territory for long enough to feed a self-reinforcing deflationary psychology in consumers.

Potential for Default

My April 2009 post argued that sovereign debt default was not a risk given the historical precedents. Since then I have had this view reinforced by the discovery of Modern Monetary Theory (Neo-Chartalism). More on that another time as I have been meaning to write about it for months, but one point it explains is why a sovereign nation that spends and issues debt in its own freely floating currency never has to default on domestic currency debt (though in very rare cases it may choose to for political reasons).

Too Much Treasury Supply?

In the prior post I addressed the then near-universal concern in the econoblogosphere that the huge pending supply of treasury debt would overwhelm demand. I prefixed my reasoning as to why the government spending (via its associated increased supply of government debt) would create its own demand for government debt by saying "my perspective on [this] I have not seen detailed anywhere else, which suggests it is novel, wrong, or simply something that no source I read has bothered to explain in detail because they thought it obvious."

It turns out that through simple step-by-step reasoning via examining macroeconomic balance sheet impacts I had discovered by accident some of the core principles of Modern Monetary Theory (Neo-Chartalism). I have been trying to learn more of the strengths and weaknesses of Chartalism since early fall but have not addressed all my questions sufficiently yet to do a post on it (I do think the strengths outnumber the weaknesses). But one proponent, Warren Mosler, puts it succinctly in red text right on his site margin: "The funds to pay taxes and buy government securities come from government spending.". I'm putting something together to help give a more detailed overview of the accounting perspective, but the bottom line is that it is the government's spending that creates the private sector's wealth that can be used to [among other things] buy government debt. When the private sector is not issuing net new debt at the same time as government is, there is no competing supply of debt, so bond prices will not be driven down by excess supply.

Will China Stop Buying?

I continue to think this concern is mostly irrelevant but don't want to go into a lot of detail. However I will give one analogy.

I recently saw a posted graphic showing recent net migration between US states over recent years (now I can't find it). Imagine someone looking at how much Californians have spent buying US Treasuries in the last year, then seeing that migration trend (I think California was net negative) and declaring "uh oh, if Californians stop buying our treasury debt, who will?!?" The obvious answer is that now there will be more Oregonians, Arizonians, etc to buy the debt.

While it's not a perfect analogy, the China scenario is similar in that the US consumer decision to buy Chinese goods is what provides the buying power to China that allows them to buy dollar-denominated investments with the proceeds. If consumers save instead of spend, or buy US goods and services instead of Chinese ones, that flow of money and potential savings simply is in the hands of US investors instead. To suggest this would generate no increase in domestic treasury demand implies thinking only central banks are "irrational" enough to buy sovereign debt and that there are not enough relative-value arbitrageurs to move prices meaningfully in response. That may hold true for short periods of time, but indefinitely? I'm not convinced.

Quantitative Easing

Quantitative easing has likely supported government debt prices to some degree, and it is winding down (for now). I argued before that QE would be an extra demand support for treasuries, but I don't think prices must reverse when the buying stops. The direct treasury purchases by the Federal Reserve have already ended, and treasuries are doing just fine since then. I also suggested that the impact of reduced supply (as the Fed takes assets off the market) would also be supportive of prices. Chartalists also make the very insightful point that QE is actually net deflationary as it reduces non-government sector income by replacing higher yielding bonds in the hands of private investors with low-yielding "money" (currency and deposits backed by bank reserves).

Sentiment

Sentiment has been wildly bearish on treasuries throughout 2009 and they remain one of the most despised asset classes. I've seen reports that short interest on government debt is among the largest of any asset class (perhaps mostly due to inflation fears). I still suspect that this doesn't leave much room for more bearishness, and leaves sentiment-driven changes much more likely to drive prices up rather than down.

Reasons This Tentative Bullishness Could Prove Wrong

To address the reasons I listed under this heading in the old post:

- "Though right now it seems politically unlikely, the government could end up trying to swap more private debt for public debt than can ever hope to be serviced by taxpayers.". This seems more and more unlikely to me, especially since I dug into the Japanese debt data and discovered that public debt issuance has exceeded private debt reduction over the last two decades and still yields plunged. Also the Chartalist perspective points out that paying taxes isn't exactly the same as servicing debt (again, more on this later), as sovereign governments are not revenue constrained.

- "...potential for significant political instability as a result of the crisis could lead to very unpredictable consequences..." Still a risk, but probably not in the near term.

- "A huge supply shock (energy, other natural resources, labor, etc) could potentially ignite meaningful inflation..." Still a risk, but the odds seem no higher than before.

- "...underfunded obligations like social security..." Still unclear on how much and how soon this could impact on treasuries, but likely not an issue in the medium term.

- "Perhaps my logic in this post is just plain wrong." On the contrary, my discovery of the Chartalist school suggests to me that the balance sheet based reasoning was accurate. Of course readers may still disagree and tell me where I'm wrong!

The Fed cannot inflate. Buy Bonds (Winterspeak)

"But the Fed cannot "drop money from helicopters". Only the Treasury can. Helicopter drops of money are fiscal policy, not monetary policy, as they create net new financial assets for the non-Govt sector. The Fed cannot inflate." ... "Even at 3% (or whatever) I recommend you buy Treasuries."Deficit Spending for Dummies

Warren Mosler walks through the Modern Monetary Theory explanation of how government sector debt issuance and spending boost private sector savings from an accounting perspective. This parallels the balance sheet reasoning in my old post.

2010 Investment Strategies: Six Areas To Buy, 11 Areas To Sell

Gary Shilling is one of the minority who have remained publicly bullish on treasuries, and he gives his reasons.

The Asset Dearth and the Japanese example and Disappearing Assets, Continued

"Why are asset prices so high? One reason is that there aren’t enough of them... The net creation of private assets has actually fallen... The only sector of the US economy presently dis-saving is the US government... the banks use the cheap credit to buy government debt, because no other kinds of debt are available."David Goldman makes the point I have made repeatedly while looking at the Z1 Flow of Funds releases starting last August in a post titled Why Treasuries Find Buyers and Interest Rates Will Not Rise (Much). For example I said: "people will buy (and have been buying) treasury debt because there are on aggregate less other fixed-income asset choices available on the market, and the new treasury issuance fills the 'hole' left by the shrinking supply of private debt as it is paid down or defaulted on."

Dave’s Top 10 Reasons to Expect the Yield Curve to Flatten

Another post (from December) by David Goldman listing reasons to be bullish on treasuries.

Finally, Paul Krugman points out back in November that "the same people now warning about the alleged Treasury bubble dismissed warnings about the housing bubble."

Conclusion

I still do not understand why even most commentators who expect ongoing private sector debt reduction (as opposed to those in the full V-shaped recovery, new bull market camp) have been so bearish on treasuries. I think it is based on false (or out of context) textbook economic arguments about government deficits creating inflation, etc. The logic as to why government debt performed well during past deleveraging cycles seems clearer than ever to me now that I have learned some of the Chartalist/MMT perspective (again, more on that later).

So the real unknown is simply whether we can escape that outcome in any sustainable way. In the early 2000s it involved a new and even larger debt bubble in housing. Maybe this time we will have the miracle of rapidly growing exports and the rest of the world quickly achieving sustainable domestic demand (both of which were positive factors for Japan) and also escape private sector deleveraging (which Japan did not). If and when evidence of that appears I'll be likely to change my case regarding treasuries.

UPDATE: Edited one phrase for clarity.